ADRIA - ITALY

The History

The History

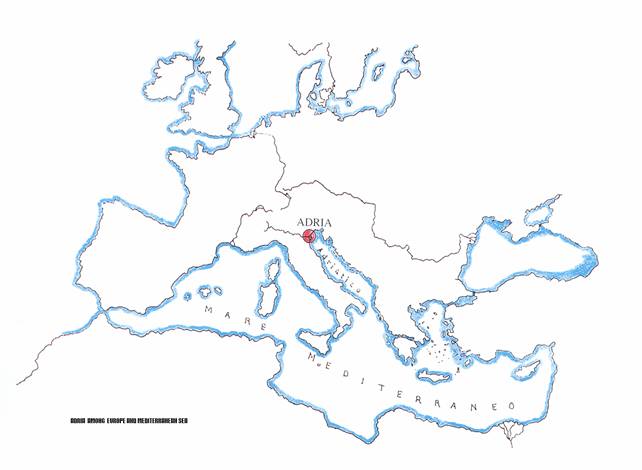

The ancient town of

Adria

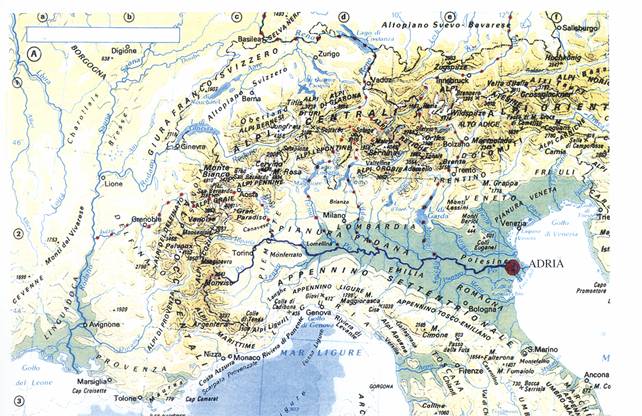

The extreme northern Adriatic area, where the

The most ancient archaeological finds concerting the port activity in

Adria date back to the 6th century

B.C. Nothing remains of the Neolithic and Palaeolithic and there are few traces

of the Bronze Age.

However, this does not mean that the territory was not inhabited before

the 6th century B.C. as the

frequent sea breaches, floods with their alluvial deposits and bradyseism may

well have swept away or buried what remained of these civilizations under the

mud. Not only did the port have the advantage of being close to the sea, but it also lay on a

The origin of the town is a much-discussed question as our territory was

populated by several civilization, thus making of Adria a cosmopolitan town.

There are also contrasting opinions about the origin of the name. It may come

from the Etruscan word atrium, making

Adria the town of the sun or of the east. As a matter of fact the Etruscans,

like all the ancient civilizations, used to orient the vestibule of their

temples and tombs towards the rising sun.

The basic population of Adria and

of its territory was likely to be Paleo-Venetian. With the coming of the Greeks

at the beginning of the 6th century B.C. the development of the town

boomed. They probably did not settle down there but merely made Adria an

emporium, the starting-point of good towards the hinterland. At the end of the 6th

century B.C. the Etruscans arrived in

search of the power they had lost on the southern Tyrrhenian coast. Unlike the

Greeks, their major concer was land-reclamation. Perhaps they connected the

five Po mouths by a transversal canal thus making inland navigation between

Adria and Mantova possible. The decline of the port began in the second half of

the 5th century B.C. because of the growing development of Spina.

After a Syracusan period, the Celts settled down here without bringing

about substantial changes. They ended up living in harmony with the local

civilizations. In the II century B.C. the Romans settled down peacefully. In 49

B.C. Adria became municipium of the Camilia tribe. They must have held Adria in

high consideration if they equipped it with a road network as is witnessed by a

milestone discovered in 1844 next to the Basilica of the Tomb. It is possible

to read the name of the consul, Publius Popilius,who ordered the via Popilia;

linking Rimini to Aquileia, to be built in 132-131 B.C. the other significant

aspect of the Roman civilization was the continuation of the land-reclamation

works begun by the Etruscans. The first century A.D. saw the peak of prosperity

for Adria followed by its slow decay as the Roman Empire declined.

From the end of the Roman Empire to the Estensi of Ferrara

It is difficult to trace the history of Adria from the decline of the

Between the 5th and 6th centuries, after a short

Gothic domination, the relations between

The tragic events which characterized the long Gothic-Byzantine

domination, epidemics and floods such as the Rotta della Cucca (589),

heightened the importance of the bishop.

Towards the end of the 7th century, when the Franks yielded the Exarchate

grounds to the Pope, the bishop of Adria, as a direct representative of the

Pope and heir to the ancient Roman municipium, assumed the dual spiritual and

temporal authority.

With the decline of the bishops and the birth of the Comunes, Adria

enjoyed a certain autonomy. Towards 1100 the town was problaby ruled by its own

statutes and councils.

As a result of the ruinous Ficarolo Breach, which occured in the mid-12th

century, the Delta assumed its present aspect.

With the Estensi of Ferrara (13th-16th centuries),

land-reclamation works were carried on.

Nevertheless a real solution to the hydraulic problems was not attained.

After having become the battle -field

between

From the domination of Venice to the Unity

The Venetians were interested in the Polesine because it bordered on

The most important intervention was the Taglio di Porto Viro

finished in 1604 wich diverted a

The soul of the conspiracy was Angelo Scarsellini, backed up by the

students Bortolo Lupati, the bold Pietro Pegolini, Dr. Alfonso Turri, Don

Costante Businaro and the count Lavia. In 1866 the Polesine came to be part of

the Kingdom of Italy.

The present-day town

The second half of the 19th century was

characterized by mechanical land-reclamation works made possible by

increasingly powerful hydraulic machines.

At the same time cultural and social initiatives

became more frequent. But, above all, means of communication improved, solving

the problem of isolation and contributing decisively to developing trade.

Between the end of the 19th century and the First World War, Adria

became a corn market.

Besides corn, wheat, oats, rice, fruits, poultry and eggs were traded.

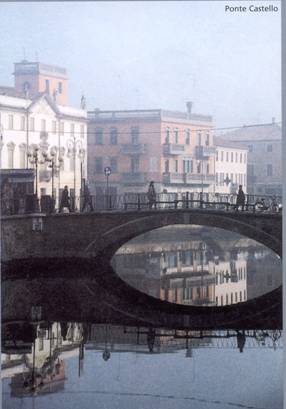

Goods were unloaded at the S. Andrea bridge, where the canal was deep enough to

sustaine the weight of boats, and stored in the warehouses standing along the

riviera.

During the early post-war period

and during Fascism the town continued in its role as a trade center but the

Second World War curbed its development: roads were in bud condition, means of

transport were inadequate and bridges were destroyed. The slow economic

recovery came to a halt because of the flood of 1951 that provoked an exodus

without return of many inhabitants. In order to improve economy the Ente Delta Padano divided the vast

estate into small farms which were mostly assigned to labourers.

In recent years Adria has recovered its ancient vocation of trade

centre, as is testified by Il Porto, a

complex consisting of more than forty shops.

In addition to large-scale distributions, small and medium activities

still exist in the heart of the town.

The resources of the town are trade, farming, handicraft, services and

tourism.

back to partnership list of schools